|

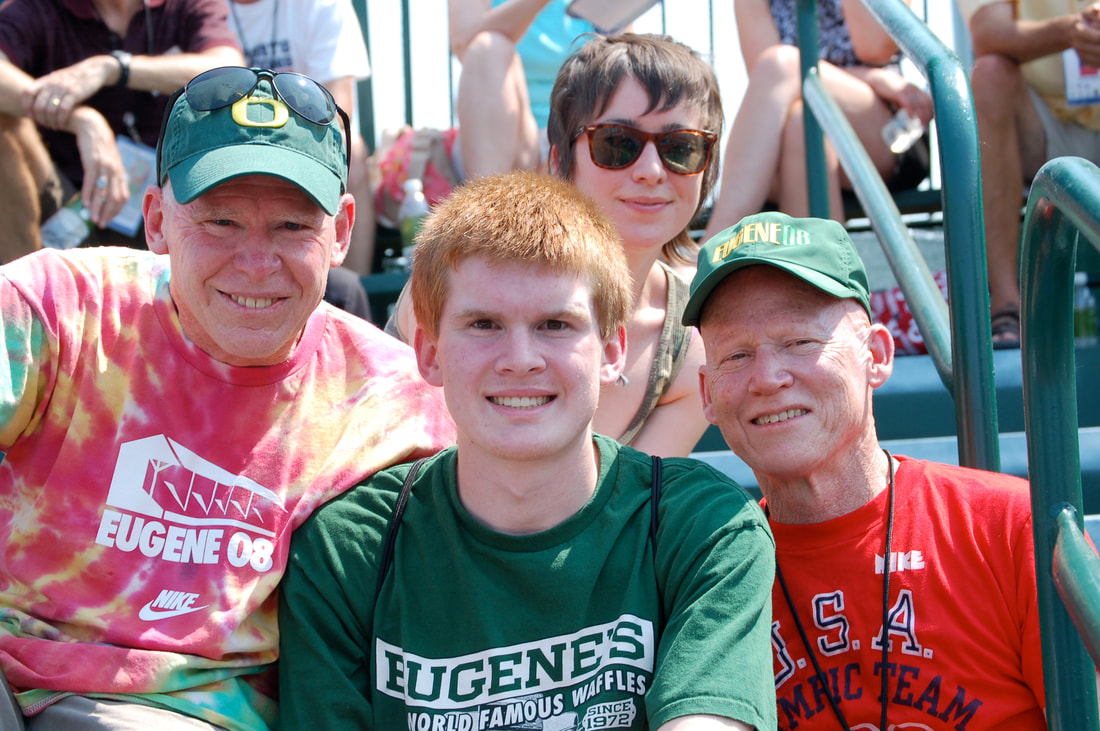

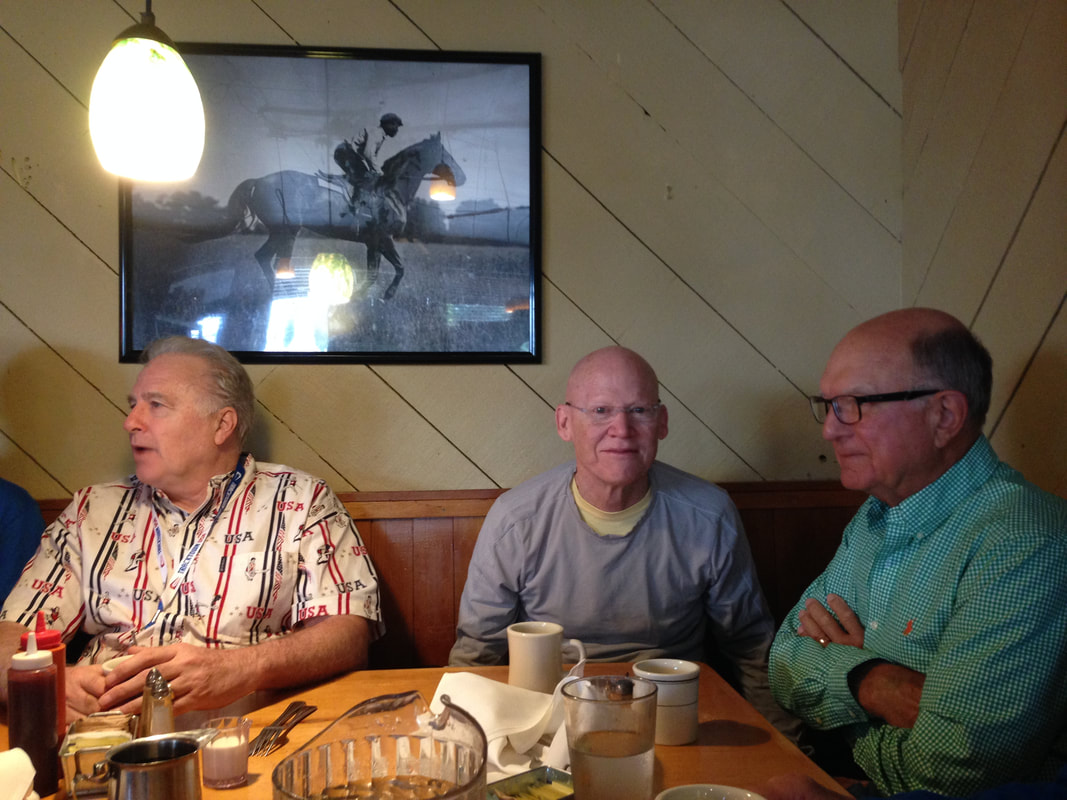

I first saw Dick Buerkle run when he was entered in the three-mile at the 1969 NCAA Championships in Knoxville, TN. A former walk-on, who had earned his scholarship by his junior year at Villanova University, he was knocked down and was not able to finish the race. I can still see him on the infield of the University of Tennessee’s Tom Black track. I wondered how injured he was that he couldn’t get back into the race. The next time I saw him in person was over three years later in Gainesville, FL, when I moved there to train with the Florida Track Club and pursue my running dreams. Dick, who was officially affiliated with the NYAC, was one of the first to embrace my arrival and we soon became morning training partners. I can vividly remember his knock on my door at 6:15 am to join him in a trip around the outskirts of the University of Florida campus—especially areas dedicated to the Veterinary College, which had cows grazing and a very unpleasant odor. I remember those sixty-minute morning runs at sub six-minute pace that Dick always counted as only 6-7 miles. He didn’t want his competition to know his actual mileage volume. I remember accompanying Dick on Sunday morning long runs and him disavowing that Barry Brown’s 20-miler was actually 20 miles. I remember he and his wife Jean inviting me over for homemade pizza or a yummy casserole, such a welcomed gesture toward another financially struggling young runner. I remember going out for ice cream as a major treat at the end of another 100-plus miles week of training. I remember going out for Friday night pizza with the Buerkles and a group, including his Villanova teammate Marty Liquori. I remember running through the roads in Pine Mountain, GA, while there for a cross country meet at Callaway Gardens. Dick’s head was bald due his case of alopecia and my hair was long and hanging past my shoulders. When attempting to purchase some groceries to make our dinner, the clerk gave us a discerning look to which Dick responded, “What you looking at?” The clerk had probably never seen a duo with such completely opposite hairstyles—especially in running apparel. After Barry Brown broke four-minutes in the mile for his first time in a Twilight meet at the Gators' track, I told Dick about it on our run the next day. He responded, "Then I can break four, too," even though his best effort was in the 4:05 range. So a couple of weeks later, with steeplechaser Dennis Bayham pacing him for a couple of laps, Dick ran 3:58.0. I remember introducing Dick to the adidas promo rep, who was in Gainesville for the USA Junior Championships, and Dick getting his first pair of “free” shoes. One of my funniest memories was when Dick and I were painting houses in Gainesville to earn some money to offset our living expenses. Not a patient painter, Dick attempted to move the ladder without removing the gallon can of paint from its perch at the top of the ladder. I watched as gravity did its job and the paint tumbled down, hitting a few rungs and splattering green paint everywhere below. Dick’s hairless head accepted a goodly amount of the green solvent. In a hurry to get to the afternoon practice with the other Florida Track Club runners, we cleaned up the mess, but Dick didn’t wash his head. Upon joining our fellow runners at the track, there was a great amount of laughter when Dick appeared. “He looked like a green Martian,” was a memorable comment. I remember when Dick broke the indoor world record for the mile, after moving back to cold and icy Rochester, NY. He was tough. How could I have wondered about why he didn’t get back up and finish that NCAA 3-mile in Knoxville? I remember Dick’s brief broadcasting career when he had his own radio show. He also commentated on various road races. I remember the joy of our families meeting (now with offspring) at the 2008 USA Olympic Trials in Eugene. It would become an all too brief tradition. Four years later at the 2012 Trials, my son, I, and Dick were just about to find our respective seats for the day’s event when I was randomly interviewed by a local TV reporter. When asked if I was sad that Galen Rupp had broken Pre’s long-standing 5,000-meter record earlier in the meet, I responded that I thought it was great. The reporter looked surprised and astonished and informed me that Pre had never been beaten by an American. I proudly responded that Pre had lost to my friend and he was standing right here next to me. Although somewhat embarrassed, Dick rose to the occasion (as he always did) and was interviewed by the reporter. I remember a week or so before the 2016 USA Olympic Trials, Marty told me that Dick would not be able to travel to Eugene this time due his progressing Parkinson’s disease. I was saddened that we wouldn’t reunite there again. But while my wife and I were running on the Amazon Trail one morning during the first days of the Trials, a man on the side of the trail called out to us. My wife responded that it was Dick. I countered that it couldn’t be, but to my surprise it was. Luckily, his son Gabe had brought him back to Eugene. We got together for breakfast with Marty, Gene McCarthy, Coach Roy Benson, Jeff Howser, Bobby Gordon, Gabe and a few others and reminisced about our days in Gainesville and other running exploits.

Sadly, that was the last time I saw my friend Dick Buerkle. My college teammate and long-time friend Lee Fidler called to inform me of his passing this morning. Richard Buerkle. You are missed already.

3 Comments

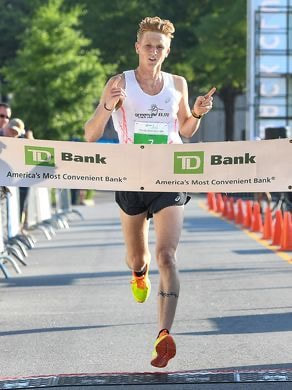

What was the origin of GTC-ELITE? MC: When Laura and I relocated to Greenville from Portland, OR, we coached at Furman University for a few years. We learned that there were a few collegiate athletes who had the talent and desire to continue pursuing their running dreams following graduation. However, there were very few options for them to do so without having to be employed full time and running more as a hobby. At that time ZAP Fitness up in Blowing Rock, NC, was basically the only post-collegiate, Olympic-development program in the Southeast. However, they had very stringent qualifying times and only spots for about ten athletes. We remembered that the Greenville Track Club had been a force in road racing in the late 1970s and through the ‘80s. They had runners such as the Daves (Branch, Geer & Cushman), to name just a few of their top performers, and Masters standouts Art Williams and Adrian Craven. Runners in the GTC singlets were always near the front of the pack in major events in Atlanta, Mobile, AL, Charleston, Charlotte, etc. They were an integral part of the evolution of the GTC. Together, with my former college coach, and the founder of the GTC, Bill Keesling, we decided to develop a resource and environment for qualifying post-collegians in conjunction with the Greenville Track Club. We consulted with other programs around the country including Pete Rea of ZAP (now ON ZAP Endurance) and developed a mission statement and business plan to present to the GTC Executive Committee. We established our own Board of Directors including some of the GTC originals such as Adrian Craven, Art Williams and Mical Embler, plus key club leaders such as Kerrie Sijion and Sam Inman. Over the years we have added a few local business leaders to the board, such as Tim Briles and Craig Bailey, and former coaches Bill Utsey and Jackie Borowicz. Right after the 2012 USA Olympic Track & Field Trials in Eugene, OR, we announced the formation of Greenville Track Club-ELITE. How do you choose athletes for the program? We researched what some of the other post-collegiate groups were doing and developed a two-tiered standard for qualifying. The performance standards are fairly hard, but not quite as fast as ON ZAP Endurance. Our mission is “development” so we wanted to make our program accessible to as many post-collegians as possible. We really don’t recruit like some of the other programs do, since we really want potential athletes to apply because we are offering something they really want to be a part of. However, once a potential candidate contacts us, we do our best to sell the positive aspects of the Greenville community. Fortunately, GVL is a good sell. If the candidate seems like a good fit, then we’ll have them visit for a couple of days to see what we have to offer and for our coaches to get a better understanding of the athlete’s running and career goals and if they fit into our program. How many athletes are in the program? It depends. In our initial business plan, we estimated that we could probably coach and support about twelve athletes. Being idealists at the time, we thought six men and six women would be optimal. However, realism prevailed and our roster varies from year to year. At one time we had eleven athletes, but at other times we have only had a few. It depends on when the athlete graduates from college and their goals. What have been some of the program’s successes? I think you have to define “success” first. A dictionary might define “success” as the accomplishment of an aim or a purpose. So, I believe we’ve had quite a few success stories. Since our inception we have experienced almost two Olympic cycles, with Tokyo 2020 now being postponed to 2021. So there have been two USA Olympic Team Trials Marathons: Los Angeles in 2016 and Atlanta this past February. We have been fortunate to have developed seven athletes who qualified for one of those events, while training under our program. So we accomplished those goals, which signifies the definition of success. In 2016, we had one young man who had previously placed 12th in the 2012 Trials marathon so we thought he had a good shot at placing in the top ten in 2016. He actually qualified on three separate occasions with half marathon performances under the standard of 1:05:00. In addition we had one male athlete and two female athletes qualify with half marathon efforts (sub-1:15:00 for women). And both women qualified in their first half marathon. Unfortunately, the LA Olympic Trials marathon was conducted under oppressive conditions. Our top athlete didn’t start due to a lower leg issue and the other three completed their first marathons with heat-slowed performances. We believe those performances were a success since the goal was to qualify for and compete in the Trials. For the recent Trials in Atlanta, we had three athletes qualify (sub-2:19:00 for men and sub-2:45:00 for women). One of our men qualified in January of 2019 at the Chevron Houston Marathon, which also qualified him to represent the US Virgin Islands in the 2019 Pan American Games in Lima, Peru. He choose to compete there and relinquished his eligibility to compete in Atlanta OTs. And he placed 12th in the international field in Lima. Our other male athlete ran his first marathon in October of 2019 at Chicago and struggled over the final miles to finish in 2:25. However, he was able to run a huge personal best three months later by placing 11th in the 2020 Chevron Houston Marathon with a time of 2:17:23. Our female qualifier only joined our program in March 2019, but ran 2:40:42 in her debut attempt (Sacramento’s California International Marathon) nine months later in December. This was an outstanding effort since she had only run a 1:18:05 half marathon the previous January before joining the program. She went on to place 49th in Atlanta in a field of over 440 women qualifiers with a personal best of 2:40:29 on an undulating course in very windy conditions. Our male athlete struggled, but finished in 2:26, which was okay considering the short turn around time following Houston (six weeks). We definitely considered these successes as our athletes experienced outstanding development in order to qualify. However, we want to continue to develop athletes and improve on our future performances at the 2024 USA Olympic Trials Marathon. Are the program’s successes primarily at the marathon distance? While we consider having seven athletes qualify for a USA Olympic Trials marathon, we have seen success at other distances on both the roads and the track. Our athletes have competed and placed well in such major events as the USA Club Cross Country Championships, the Peachtree Road Race (Atlanta), Chevron Houston Marathon, Bloomsday (Spokane), California International Marathon (Sacramento), the Great Cow Harbor 10K (NY), Tufts Healthplan 10K (Boston), USA 25K Championships (Michigan), and Cooper River Bridge Run (SC), to name a few. Just this year, 2020, two of our athletes set South Carolina State Records--one for the women’s 15K and the other being the men’s half marathon. Almost every athlete that has completed at least two training macrocycles (approximately a 12-month period) has produced personal bests. One athlete dropped over two minutes in the half marathon, while another over seven minutes in the marathon. Our athletes have run personal bests in distances ranging from 1500 meters through the marathon. Our program records are fairly good from 3,000 meters up to the marathon for both men and women and continue to get better. Has everyone been successful? With full disclosure, we have had a few athletes that the fit just didn’t work and they departed before their first year—and some even before completing one training cycle. What do you mean by “the fit didn’t work?” Post-collegiate running is interesting. If you are really, really good and maybe placed top five at the NCAA DI championships, you have an outside shot at being accepted to one of the top training groups (NIKE’s Bowerman Track Club, Hansons-Brooks Original Distance Project, HOKA’s Northern Arizona Elite, ON ZAP Endurance . . .). When we established our program, we targeted the next tier below that level. Although in the past we attempted to recruit a few graduating collegiate athletes, we later decided to let the athlete contact us if they want to prolong their competitive running career. That change leads to having athletes that really want to postpone their full-time working career and apply. We know they are probably more focused. So, to attempt to answer the question--some athletes like the concept, but not the reality. It sounds good to “go pro” as some like to say, but the reality is that running is really not much of a “professional” sport. Sure, the very top athletes can make some real money, but most have to find various ways to support their habit. Not too many runners earn enough to be considered “professional”, which would represent earning a living wage. Our athletes all have part-time employment. If an athlete doesn’t have the focus to make sacrifices, including lack of money and social time, they probably won’t fit in our program. And they need to believe and trust in our coaches’ philosophies. That is extremely difficult in the “internet” environment. Athletes are sometimes influenced by what others are doing in their training. As the old adage goes, “the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence.” What percentage of athletes don’t fit? First, let’s look at the positives. We’ve had a lot of athlete’s complete their 24-month contract agreement. One woman was with our program for four-and-half years before departing to marry and relocate to where her husband works. She recently qualified and competed in the USA Olympic Trials Marathon with her new training group. So, that was a success. At this juncture, about 44% of our athletes have completed their initial contract agreements before either staying or moving on with their life. However, about 25% didn’t stay for an entire year, before deciding to move on. And about four athletes never ran a race for us as they arrived injured. That being said, quite a few have remained in Greenville. That was one of our objectives when we established the program, to attract young, smart people to our city and hopefully have them become part of our community. I believe we have ten former members of our program living and/or working in GVL now. That’s over 35%. There is actually constant turnover with many of the other post-collegiate programs. You just usually don’t hear about athletes departing. So basically, it is like sports radio host Colin Coherd has stated, “It’s all about fit.” What are some of the reasons that athletes depart? There are various reasons. Sometimes an athlete realizes that they aren’t going to reach the level of performance that they dreamed they would. Dreams don’t always come true, but it is better to dream big than not. Sometimes it is more about lifestyle or desired lifestyle. We’ve had a few that desired to marry and that life change required either moving or more financial support, such as a full-time job. Other times, the athlete doesn’t “buy into” our training methods. That’s always a disappointment as we do our best to explain how we train during our early phone conversations and especially during their interview process when visiting us in GVL. As author and high performance coach Steve Magness has stated, “One of the most important factors determining whether a training program will work or not is belief. If you don’t have buy-in, even if the training is perfect, it’s not going to work.” We’re not a high mileage program, so some believe that they need more mileage. We actually don’t count mileage per se, as we base our training on bioenergetics (energy systems) and the appropriate time needed for each stimulus to produce the desired adaptation. That being said, we’re not a low-mileage, high intensity program either. We believe in optimizing the appropriate amount of volume + intensity to meet each individual’s athlete profile, while still operating in a group environment as much as possible. There is “power in the group.” That is one of our program's Maxims: The Power is in the Group - No one has ever accomplished anything on his or her own. There is no such thing as individual performance. We all need some help to become great. What is your training philosophy? Our training philosophies are time-proven, but we continue to evolve. For example, we added what we call “The Lactate Shuttle” workout, which is based off of Peter Thompson’s “New Interval Training” system. It has proved to be successful when used in the appropriate sequence of workouts and is now a “staple” in our program. While Coach Laura repeatedly states that “coaching running is not rocket science,” I like to add that “good coaching uses running science.” And science informs us that recovery is an important tool in our toolbox. So instead of a three-legged stool of “intensity, duration and frequency,” we have more of a chair with four legs, with that fourth leg being appropriate recovery. We incorporate three “recovery” days per seven-day microcycle. We also prescribe a good amount of ancillary work in the form of Dynamic Movement Drills, Dynamic Flex Drills plus three sessions per week in our F.I.T. Garage. The focus of this work is on the Biokinetic system, which expert coach and educator Peter John L. Thompson has labeled “The Fourth Energy System”, with the other three being Bioenergetics (Phosphagen, Glycolytic/non-oxygenated and Aerobic). The Biokinetic work includes movements promoting the leg/muscular stiffness and also balance of the kinetic chain. While our initial expectations for the program included athletes developing for about four years or eight training macrocycles, we’ve found that two years is about the actual average. That seems to be a long time for young people just coming out of college who don't attract a major footwear contract. That being said, the ones that do remain longer in our program seem to come much closer to reaching their goals. How many of those that depart continue to run at a high performance level? We’ve had a few continue at a high level and continue to improve after they left. We had four former ASICS GTC-ELITE athletes (alumni) qualify for the recent Atlanta OTs so those athletes have continued to develop and improve in their new environment. We are proud of their accomplishments and hope that their time in our program assisted somewhat in their continued development. Endurance running is about consistency and our program might have provided the coaching and resources that led to consistency. One male athlete has become a very high-level triathlete at the national level and also continues to place well at local and regional road races. There are others that just decided to move on with their lives and run for fitness. But, a few of our former athletes have continued to run and compete at the local level, which is good. One continues to use Coach Laura for her training advice. You mentioned resources. Can you explain? Sure. First, we provide coaching expertise. Laura, Bill and I have many years of running and coaching experience and provide such at no cost to our athletes. We’ve coached at the national, post-collegiate, Olympic-Development, collegiate and high school levels. We have been fortunate to have an excellent partner in ASICS, which has provided footwear and apparel almost since our inception. We also provide housing to those athletes who meet that qualifying standard and choose to live in our athlete residence. We have a workout facility that we call the F.I.T. Garage. F.I.T. actually is an acronym for Functional Innovative Technology. In the FG we have many types of equipment that we utilize for our ancillary training. We also have a treadmill and an ElliptiGO on an indoor trainer. (We have a couple of ElliptiGOs for outdoor use, too.) Our resource circle involves partnerships with Performance Therapy (Brad McKay and staff) for soft-tissue issues and maintenance, Carolina Spine & Rehab (Michael Shride) for structural alignment, and ATI’s Running Academy (Kent Kurfmann) for gait analysis. We also value our other partnerships with Final Surge (online training/scheduling platform), Cocoa Elite (recovery protein products), Roll Recovery (recovery apparatus), NormaTec (recovery boots) and the DorsiFlex (lower leg and foot stretching device). A program like this must cost quite a lot. Where does your funding come from? That’s correct, a program like our’s is dependent upon funding and our funding is totally from corporate, foundational and personal contributions. We are very fortunate to be under the umbrella of the Greenville Track Club. Obviously, we couldn’t have established the program without their support and financial contributions. As stated before, ASICS has been a wonderful partner. They have provided the high quality footwear and apparel that our athletes depend on. Over the years, we have had generous individual contributors who made charitable donations to assist with our travel and training expenses. They have been vital to our organization. We were fortunate to have received a one-time grant from the Road Runners Club of America to assist us in preparing for the 2016 Olympic Trials. Corporate organizations such as Greenville Health System (now PRISMA), ScanSource and Joy Real Estate have provided funds and job opportunities for our athletes. And recently we were honored that the Borch Foundation (Furman University graduate Chris and his wife Andrea) made a major contribution. What does the future look like?

That is an interesting question during this current period of uncertainty. We were extremely fortunate to have participated in and expereinced the 2020 USA Olympic Trials Marathon on the final day of February, since the severity of the novel cornavirus COVID-19 had not induced “social distancing” just yet. As “social distancing” and “shelter in place” guidelines became necessary, all competitive opportunites were either cancelled or postponed. That obvioulsy has changed our future plans. Our athletes are coping as well as can be expected, but some of our normal training venues have been restricted or closed. However, our athletes have continued to train—just not in groups. We hope that we will expereince a positive change in our nation and globallly soon, but expect that the “new normal” may be a bit different going forward for some time. With that being said, the restricted travel and undertainity has changed some of our plans. Plus, some of our athlete contract/agreements expire in July. A lot depends on what the future holds regarding competitive opportunities. We fully expected one of our athletes to qualify for the USATF Olympic Track & Field Trials this coming June, but that event has been postponed and rescheduled for 2021 due to the current health situation and the postponement of the Tokyo Olympics unitl 2021. However, that will give us more time to build strength and continue to develop and improve. Also, due to the expectation of the NCAA allowing this year’s seniors to return in 2021 for the Outdoor Track & Field season, we do not anticipate having recent graduates join our program this year. However, we do have a few available slots for aspiring athletes who meet our qualifying standards and want to get to the next level. I had the honor of returning to Atlanta, GA for the 50th anniversary of the iconic Peachtree Road Race on July 4th, 2019. Forty-nine years ago I traveled to Atlanta from Greenville, SC, where I was a student at Furman University, to run in the first Peachtree Road Race. Dr. Tim Singleton organized the event, which was run from the old Sears parking lot on Peachtree to downtown Atlanta (uphill most of the way). With a starting time of 9:30 am (and actual start a little later due to day of race registrations) it was a hot trot on one of Atlanta major roadways. After attempting to run just behind future Olympian (1972) Jeff Galloway for the first mile or so, I had to let him and Georgia Tech's Joel Majors go and became content to remain in third place until the finish. The times were slow, due to the July heat and humidity and the challenging route. For the 50th anniversary, the Atlanta Track Club generously invited me and the others from the "Original 110" finishers back to celebrate this milestone edition. The 2019 race had 60,660 finishers and is the largest fully-timed race in the United States. It was great to see about 40 of those "Original 110" finishers at the Tuesday morning press conference and reception hosted by the Atlanta Track Club. Many thanks to Rich Kennah (ATC executive director and race director) and Janet Monk (who organized the "Original 110" communications and gathering). Although I run daily, I do not race anymore and prefer coaching our ASICS Greenville Track Club-ELITE athletes now. However, I couldn't pass up the opportunity to run down Peachtree on the 50th anniversary. I enjoyed the amazing crowds of spectators lining the course, the various bands representing the 70s, 80, 90s, etc., and especially spotting and crossing the finish line on 10th Street. I finished 6,368th this time (almost in the top 10%) in a pretty slow time of 55:30. However, I was pleased and honored to cross the Peachtree finish line once again. As an interesting side note: I ran the 1970 P'tree in a pair of Tiger (now rebranded as ASICS) Marathons and ran the 50th edition of the race in ASICS DS-Trainer 24s.

For coaches, teachers and parents of high school runners, Greenville Track Club-ELITE coach Laura Caldwell has authored an article regarding tips for college recruiting. Caldwell is one of the directors for the Women's Running Coaches Collective, a group of current and former elite runners and coaches, whose mission is "to support, unite, inform, inspire, encourage and empower women coaches at all levels of our sport."

You can read the article by accessing the following link: https://mailchi.mp/a27412bd75fd/womens-running-coaches-collective-needs-you-239757?e=fc4117f48d Women coaches are encouraged to sign up for bi-monthly emails from the WRCC. Sign up for our list! The WRCC can also be found on Facebook as "Women's Running Coaches Collective". And you can add to the conversation at their email address - [email protected] PLEASE tell them what you would like to learn as a coach? What information would you like to make your job more of a success? Who would you like to have interviewed? The Women's Running Coaches Collective

This is a portion of an article that originally appeared in the January/February 2016 issue of Running Times Magazine and was authored by Phillip Latter.

When Mike Caldwell, Greenville Track Club-ELITE Head Coach brings recruits to the club's South Carolina campus, he discovers they're not worried about adjusting to life in a small Southeastern city or leaving the comfort zone of college to train in a professional group. Their biggest worry? It's the recovery days. Twice a week they run 45 minutes total. That's it. For elite college runners used to averaging 12-15 miles per day, this sounds downright crazy. The key to Caldwell's system is a strong delineation between workout days and recovery days. Durning hard interval sessions around 5K pace, for example, his athletes will cover five to six miles in volume, as opposed to the more traditional three or four miles. In order for his runners to handle that volume of quality, Caldwell believes they need to be fresh heading into the sessions. "I think a lot of people just don't understand recovery," Caldwell says. "Our recovery days are vital to our system. We're able to run hard on our hard days (because) we only ran 45 minutes on Wednesdays and Fridays."  During my many years of running and coaching I have observed thousands of races and countless marathons. One of my pet peeves is hearing, “ I was on pace for ‘x number’ of miles before I slowed down to finish in “y time.” “Yes, sure you were,” is my non-verbal response as I attempt to smile and listen to another poor excuse for improper pacing. What is proper pacing? Well, simply stated, it is not going out faster than you finish. Throughout the history of competitive running, runners have sprinted from the starting line only to deplete their appropriate energy systems and slow to an unfavorable pace. You can see it at almost every race you attend. The culprits’ brains just don’t seem to be able to figure out that going out too fast is NOT a good strategy. Although this happens in races of all distances, it is especially true in the marathon. Even many of the sub-elite runners provide their post-race explanations such as, “I was on qualifying pace for 21 miles, but then I began to slow down. I’m not sure why.” Wow! What a mystery. You ran too fast for the first part of the race and for some unknown reason you can’t understand why you slowed down. As a professional coach, this is where I like to explain why a negative can be a positive. The best way to run almost any race over 800 meters in length is to go out at a slower pace than the pace you can finish at. Physiologically, consistent pacing is the best way to run efficiently. Having a faster second half of your race produces a “negative split.” However, in the 800 meters research data has shown that in championship competition the first 400 meters is usually a little faster than the next, and final, 400 meters. National and Olympic caliber athletes usually have approximately a 2-second “positive” split between their first and last lap of 400 meters. For example, an athlete running 1:50.0 for 800 meters will probably run something similar to 54 seconds for the first 400 and 56 seconds for the last 400. This isn’t always true, but has been demonstrated over the last couple of decades. However, when moving up in distance to the 1500 meters, almost all of the top competitors run their fastest segment of the race over the final 200 meters. “That’s because they are kicking,” is the common runner’s observation. True, and the kick over the final 400 meters usually leads to a “negative” split for second half of the race. When observing world-class runners in the 5,000 or 10,000-meter events, the final 400 is usually much faster than any other lap during the race. It is not uncommon to see the top 5000-meter finishers covering the final 400 meters in less than 53 seconds in an event where the average lap is in the 62-64 second range. In most of these races, the first 400 is very close to the final average time per lap. “So what about the half-marathon or marathon?” you might ask. For longer distances, proper pacing is just as, or even more important. A great example was the 2016 USA Olympic Team Marathon Trials in Los Angeles. Former Brigham Young University star and current BYU professor Jared Ward used his almost perfect pacing strategy to earn one of the three coveted spots on the USA Olympic team that later competed in the Rio Olympics. Not surprisingly, Ward wrote his thesis on pacing for the marathon. At the 2017 Chicago Marathon, winner Galen Rupp ran “negative” splits to win convincingly over some top talent, who had much faster times then he had on his resume. After covering the first 5K in a rather slow 15:43 (5:04 per mile) the pace gradually increased and the leaders passed the halfway point of 13.1 miles at 1:05:49 (5:01 per mile). At 30K, there was still a pack of ten competitors and Rupp decided to wait until 35K (7K from the finish) before increasing his tempo. He then ran the next 5K in 14:25 (4:38 per mile) to break his competition. And for some insurance, he ran the 41st kilometer in an amazing 2:38 (4:27 per mile pace). His second half-marathon split was 1:03:30 for a negative split of 2 minutes 19 seconds. The next month at the New York City Marathon Shalane Flanagan utilized a similar strategy, although not really pre-planned, to become the first USA woman to win the NYC event in 40 years. After a first half-marathon split of a rather slow (for elite women) 1:16:18, she ran 1:10:35 for the final 13.1 miles. That split included incredible mile splits of 5:09, 5:08, 5:11 and 5:04 for miles 22 through 25. Her 5K split from 35 to 40K was a fast 15:57—a 5:09 per mile pace. Now those really are NEGATIVE splits with a POSITIVE result. So how do we use this information from the super elite for our own performances? Train properly and use a race strategy of running the first half of your race no faster than you run the final half. Author Mike Caldwell is director/coach of ASICS GTC-ELITE and this article was written for and originally appeared in PACE Running Magazine's Winter 2017 issue.

As a professional running coach, I attempt to keep abreast of any new concept or practice that may enhance my athletes’ training and performance. Recently authors Brad Stulberg and Steve Magness published their collaborative work entitled “Peak Performance.” The book’s cover highlights the title with the phase, “Elevate your game, avoid burnout, and THRIVE with the NEW SCIENCE of SUCCESS.” With that noble objective, how could I not read and learn how to apply their concepts to our post-collegiate, Olympic development athletes. But why would this book be any different from the many that tout the “transformation” of your life and lead you to the top of the mountain in your respective endeavors? What first caught my eye was the co-author, Steve Magness. Steve was a former high school track phenom, who never progressed much from his 4:01 mile as a schoolboy. However, he has become one of the top coaches in the country and published his first book The Science of Running in 2014, which seemed to be a more formal version of his articles first published on his website, Scienceofrunning.com Quoting from the book’s cover inner sleeve, “A few common principles drive performance, regardless of the field or the task at hand. Whether someone is trying to qualify for the Olympics, break ground in mathematical theory, or craft an artistic masterpiece, many of the practices that lead to great success are the same.” I will admit that from my past readings there is nothing really groundbreaking in the book—that is some new concept that has been recently discovered. However, the information is presented in a logical, pragmatic and orderly way that should allow the reader to contemplate the information and begin to apply the concepts in their own quest for reaching their peak performance. The book is organized around three key concepts:

The first section reiterates the core principle of physiological performance improvement: STRESS + REST = GROWTH. This equation has been one of our guiding principles within ASICS Greenville Track Club-ELITE since our inception. We base our training philosophy on this equation and it has become one of our maxims. The authors explain, “Systemically grow by alternating between stress and rest.” This concept is similar to what veteran coaches would link to legendary coach Bill Bowerman’s “Hard/Easy” training concept. They provide some easily memorable bullet points describing basic concepts such as: “Stress Yourself by seeking out ‘just-manageable challenges’ in areas of you life in which you want to grow.” These “just-manageable challenges’ are those that barely exceed your current abilities. Once you feel that you can achieve those goals, increase the challenge. This might seem obvious to many, but sometimes runners set their goals so high, that they get discouraged when they don’t achieve them. One area that I really liked was the idea to “cultivate deep focus and perfect practice.” This includes the authors’ words:

In conjunction with the “Stress Yourself” concept is “Have Courage to Rest.” In this section the authors discuss how to use meditation, being mindful, taking the appropriate breaks and prioritizing sleep. There has been a lot written about the importance of sleep, including Arianna Huffington’s 2016 bestseller The Sleep Revolution. However, many runners still do not seem to understand and embrace the importance of sleep in the recovery and adaptation cycles so vital to performance improvement. Peak Performance provides some excellent advice and guidelines regarding this important concept. One of the things that I really liked about the book was the bullet point summary of all the principles identified and explained in the book. This section is extremely useful as a coach to revisit on a frequent basis as we continually attempt to improve our athletes’ (and our own) performances. Author Mike Caldwell is director/coach of ASICS GTC-ELITE and this article was written for and originally appeared in PACE Running Magazine's Fall 2017 issue. One of the unique characteristics of great coaches is that they continue to learn. Interestingly, if you listen to some of the “old timers” in our running community and communities around the country, they will tell you “to be a good runner you just have to run more miles.” While the appropriate volume (distance run during a specific period of days, week, months, etc.) is necessary, there are other important aspects that contribute to high performance running. Recovery is just as important as frequency, intensity and duration. Fortunately, over the past decade more tools have become available to aid in the recovery process. I will highlight a few of the “tools of our trade” that we utilize with our post-collegiate, Olympic development athletes on ASICS Greenville Track Club-ELITE. The R8 and R3 devices and Mats from Roll Recovery Roll Recovery’s products were developed to aid in the recovery process. Their first product, the R8, is a unique device that uses spring-like forces to “dig deep” while massaging your muscles. Many runners use “stick-like” devices, but from our experience the R8 works even better. The R3 is a basically a roller for the foot, although it can be used on other appendages, too. Its design promotes the correct rolling pattern for your foot and is extremely useful in preventing and/or rehabbing the foot due to plantar fasciitis. The Roll Recovery mat is hexagonal shaped and also folds up so that you can carry it easily to use immediately following your cool down. It is wide enough to accommodate more lateral movements than a normal yoga mat. The DorsiFlex If the R3 is not enough to aid in the rehab from or prevention of plantar fasciitis, then the new DorsiFlex device is a must have. Designed by former national steeplechase standout Jim Cooper, an engineer by trade, this is the second production iteration of the product. While the initial version worked extremely well, it was made of wood. The new version is made of sturdy metal and also adjusts to allow multiple degrees of inversion or eversion of the foot. Testimonials have been extremely positive. The ElliptiGO bicycle For those of you who follow the amazing exploits of Meb, you are probably aware that his utilization of the ElliptiGO has been instrumental in his longevity as a super-elite marathoner. Not to be confused with an indoor elliptical unit, the ElliptiGO is a moving version that allows you to ride outside and experience much of the same sensations and benefits of actual running. And since there is no foot strike or pounding, it is extremely beneficial for those with minor injuries or adding volume for the healthy athlete. We have used both our outside ElliptiGO and our inside one (set up on a Kinetic Road Machine to simulate actual riding) for our athletes during injury or to add a second daily workout. NormaTec Recovery Boots Sometimes your legs need a little assistance to initiate and quicken your recovery cycle. For those of us who don’t have access or the financial means to have a post workout massage, the recovery boots by NormaTec are perfect. The NormaTec PULSE Recovery Systems are dynamic compression devices designed for recovery and rehab. They use compressed air to massage your limbs, mobilize fluid, and speed recovery with their patented NormaTec Pulse Massage Pattern. The athlete will first experience a pre-inflate cycle, during which the connected attachments are molded to his/her exact body shape. The session will then begin by compressing the feet, lower leg, or upper quad. Similar to the kneading and stroking done during a massage, each segment of the attachment will first compress in a pulsing manner and then release. This will repeat for each segment of the attachment as the compression pattern works its way up the limb. You can actually rent time to use the NormaTec boots at Frigid Cryotherapy in Greenville. Cocoa Elite Recovery Mix

While chocolate milk has been one of our favorite post-workout recovery drinks for many years due to favorable carbohydrate/protein (3-4/1) ratio, we have recently begun to use products from Cocoa Elite. Research has indicated that the flavanols found in cocoa may produce a positive impact on health due to their associated antioxidant properties. Flavanols help support healthy blood vessel function and the overall health of the cardiovascular system. Cocoa Elite seems to have the right combination of carbohydrates, proteins and a small amount of fat that provides the best nutrients to aid in recovery. Friends and supporters of ASICS GTC-ELITE can purchase Cocoa Elite products with a discount by using the code "GTC-COCOA" on their website @: https://shop.cocoaelite.com/collections/all Author Mike Caldwell is director/coach of ASICS GTC-ELITE and this article was written for and originally appeared in PACE Running Magazine's Summer 2017 issue.  Almost everyone has pet peeves—little things that continue to annoy you. As a professional coach and exercise scientist I have quite a few. One of the most annoying is listening to coaches and other so-called “fitness experts” tell their athletes that lactic acid causes them to slow down or make their legs sore. It is a myth that began many years ago. Way back in 1922 Nobel Prize winners Dr. Otto Meyerhof and Dr. Archibald Hill independently conducted research in which electric shocks were administered to severed frog legs. Initially the frog legs would twitch before eventually becoming still. Upon inspection, the severed frog legs were awash with lactic acid. The scientists deduced that since the severed legs were not receiving a supply of oxygen from the original organism, then the anaerobic energy system produced “lactic acid,” which led to a condition of “acidosis.” It was then assumed that “acidosis” shuts down muscle fiber contraction. Coaches and runners readily accepted this theoretical finding and then spent nearly sixty years attempting to train to overcome the effects of lactic acid. It wasn’t until 1985 that University of California at Berkeley physiologist Dr. George A. Brooks demonstrated that lactate is actually a valuable fuel for our muscle fibers and not the villain it was assumed to be. First, you must understand that lactate is for all practical purposes lactic acid minus a hydrogen ion. The new theory was that lactic acid splits to create both lactate and hydrogen ions; lactate is good and hydrogen ions are bad. So lactic acid still remained somewhat of a villain to athletic endeavors. Then in 2004 Dr. Robert A. Robergs and others presented another blow to the dwindling ill-famed reputation of lactic acid. In their paper they claimed that lactic acid “is never created during anaerobic energy production.” Instead, the dreaded hydrogen ions arise independently of lactate. And, lactate actually decreases acidosis in muscle tissue both by consuming hydrogen ions and by pairing with them to exit the muscle fiber with the assistance of transport proteins. Dr. Laurence A. Moran, a biochemist and textbook author, celebrated Robergs’s, (and associates) findings by proclaiming, “The important point is that lactic acid is not produced in the muscles so it can’t be the source of acidosis.” More recent research has continued to challenge the role of acidosis as a cause of fatigue. McKenna and Hargreaves stated, “Fatigue during exercise can be viewed as a cascade of events occurring at multi-organ, multi-cellular, and multi-molecular levels.” The current thinking is that lactic acid is not a villain at all. Instead lactate is a valuable energy source, which can be used to continue muscle contraction. It is formed and utilized continuously in diverse cells under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. So, lactate itself does not cause fatigue but certain accompanying products might. The accumulation of hydrogen ions and the corresponding lowering of pH is most likely the cause of acidosis, which has a direct relationship with muscle fatigue--an inability to generate high muscle contraction forces and sometimes producing a burning sensation in affected muscles. Smart coaches and athletes have adapted their training methods to increase the utilization of muscle (and blood) lactate. Our own experience with training our post-collegiate, Olympic development athletes is that we have targeted very specific training to increase lactate utilization during both training and competition. Our “Lactate Shuttle” sessions are a core part of our training programs. We utilize “Lactate Shuttle” sessions to “buffer” the effects of hydrogen ions within the muscle fibers and enhance the movement of lactate within and between the cells. Lactate is a fuel, not an acid, but is still closely associated with the production of hydrogen ions. Lactate and hydrogen ions leave the muscle fibers together escorted by specialized transport proteins. Our “Lactate Shuttle” workouts are targeted to increase these transport proteins, therefore increasing the facilitated diffusion across the cell membrane and improving lactate dynamics. Lactate DOES NOT cause muscle soreness. Since lactate is a fuel source, it is utilized quickly and removed from both muscle tissue and blood soon after even intense exercise bouts. It does not linger for days and is usually reduced to “normal” levels within an hour post exercise or much sooner if a cool-down session follows. In summary, if your coach or trainer states that “lactic acid” is causing you to fatigue or produce sore muscles, you should be cautious, as they are uninformed and propagating a “myth.” Author Mike Caldwell is coach/director of ASICS GTC-ELITE and this article was written for and originally appeared in PACE Running Magazine.  When does running 4:04 for 1600 meters leave you out of the money? Well, in the men’s Olympic 10,000 meter final to list just one instance. For those of you who have continued to read, you know that is four laps of the track and just nine meters short of the imperial distance known as the mile. For those of you who watched the recent 2016 Olympics in Rio, there were many exciting Track & Field events, including multiple world records. On the opening day, the women’s 10,000 meters set the tone with an amazing world record run by Ethopia’s Almaz Ayana. Following a rarely seen opening 5,000 meters of 14:46 by Kenyan rival Alice Nawowuna, Almaz did the unthinkable and increased her pace to cover the final 5,000 in 14:30. Her amazing final time of 29:17.45 broke the long-standing world record of 29:31.78, set by China’s Junxia Wang from September 8, 1993. Ayana covered the 10th and final kilometer (1,000 meters) in a speedy 2:54.57. That is averaging 69.8 per 400 meters for the final K and under 2:57 per K for the entire 10,000 meters. The men’s 10,000 was conducted the following evening and featured Great Britain’s Mo Farah and his attempt to repeat one of his gold medals earned at London’s 2012 Olympic Games. Track experts anxiously waited to see if the rumored strategy of the Kenyans teaming together to wear down the MoBot and tame his well-known final “kick”. As everyone is very aware now, they were not able to do so. It is always interesting to read or hear comments by many non-elite and even former very good runners regarding such races. Many opine that someone should have run hard and fast earlier to ensure that Mo used more energy and couldn’t kick. More than one commenter espoused that American Galen Rupp should have thrown in a surge earlier and by doing so he would have been able to place among the top three and medal for the USA. Another stated that the American should have gone out at 26:40 pace and that would have garnered more success than his (Rupp’s) 5th place finish. Hogwash! It has been well documented that a faster than needed earlier pace in distances above 800 meters is not successful in producing top finishes in more than 90% of competitions. What many observers didn’t quite grasp was that the men’s Olympic 10,000 was indeed a “fast” race. Let’s take a quick look at Mo’s 1,000-meter splits: 2:58.7, 2:49.8 [5:48.5], 2:42.8 [8:31.3], 2:43.7 [11:15.0], 2:39.7 [13:54.7], 2:43.2 [16:37.9], 2:41.7 [19:19.6], 2:42.0 [22:01.6], 2:35.4 [24:37.0], 2:28.2; for a final time of 27:05.17. And remember, he took a tumble to the track during the third kilometer, but got back up quickly and resumed his quest. Another view would be Mo’s final 2K segments. He covered the final 2,000 meters in 5:03.6 or an astonishing 60.72 per 400 meters, the final 1600 meters in 4:01.2, the final 1200 meters in 2:59.0 (59.6 per lap), the final 800 in 1:56.6 (58.3s), the final 400 in 55.3 (now we’re moving), the final 200 in 27.3 and the final 100 in 13.4. So why did it come down to a final kick over the last 400 meters? Why not? In almost every running event over 200 meters, the runner who covers the final 400 meters the fastest (if within reasonable striking distance after completing the penultimate lap) either wins or comes very close. The trick is staying with the lead pack to be able to attempt a “kick.” For many reasons, many “track fans” despise a slow early pace and desire what they term an “honest” pace from the start. They believe that is a more honorable method for racing. Well, the British believed that marching in unison, while wearing attractive red coats, was an “honorable” method to fight a battle. And how did that work out in the American Revolutionary War? Not so well. The object is to win, not to see who can run the fastest for the first portion of the race. In Rupp’s case, he covered the final 1600 meters (remember that’s almost one mile) in 4:04 (approximately a 4:05 mile) and could only garner 5th because four others closed just as fast or faster. But what if had run faster earlier in the race? Then he would not have been able to close as fast as he did and would more than likely have finished 6th or worse. Many opined that Rupp couldn’t kick. That depends on how you classify a kick. He did run a 56-57 second final 400 meters and a sub 1:59 final 800, so that seems to be a pretty decent “kick.” But Farah, Paul Tanui, Tamirat Tola and Yigrem Demelash were just a little bit faster on that night. Fifth in 27:08.92 was still a very good effort for the man who is probably the USA’s greatest track distance runner, if you look at his consistently fast times and top performances over the past decade. Postscript: Rupp later earned the bronze medal in the Olympic Marathon. Mike Caldwell Note: this article was originally published in the Fall 2016 issue of PACE Running Magazine. |

AuthorMike Caldwell is the Director and one of the coaches for ASICS Greenville Track Club-ELITE. For more on Mike please visit his page on this website. Archives

June 2020

Categories |

- News Blog

-

About Us

- Mission, etc.

- Our Four Pillars

- Our Maxims

- Contact Us

- Support Us

- Board of Directors

- Qualifying Standards

- FAQs

- Apply

- Olympic Trials Qualifiers

- NCAA Champions

- NCAA All Americans

- Club Records

- SC State Records

- Performance Lists

- Victories

- USA Road Championships

- Program Highlights >

- Community Involvement

- Legacy Running Camp

- Schedule

- Coaching & Training

- Laura Caldwell Fellowship

- Current Athletes

-

Alumni

- Wallace Campbell

- Calista Ariel

- Chass Armstrong

- Trent Binford-Walsh

- Ryan Bugler

- Chris Caldwell

- Josh Cashman

- Shawnee Carnett

- Frank DeVar

- Nicole DiMercurio

- Kate Dodds

- Dylan Doss

- Ricky Flynn

- Emily Forner

- Adam Freudenthal

- Dylan Hassett

- Mark Leininger

- Mackenzie Lowe

- Zach Mains

- Cristina McKnight

- Avery Martin

- Tyler Morse

- Joe Niemiec

- Alison Parris

- Victor Pataky

- Annie Rodenfels

- Ryan Root

- Kimberly Ruck

- Austin Steagall

- Carolyn Watson

- Chelsi Woodruff

- Blake Wysocki

- Pics & Vids

- Sponsors

- Greenville, etc

- Social Media

- News Blog

-

About Us

- Mission, etc.

- Our Four Pillars

- Our Maxims

- Contact Us

- Support Us

- Board of Directors

- Qualifying Standards

- FAQs

- Apply

- Olympic Trials Qualifiers

- NCAA Champions

- NCAA All Americans

- Club Records

- SC State Records

- Performance Lists

- Victories

- USA Road Championships

- Program Highlights >

- Community Involvement

- Legacy Running Camp

- Schedule

- Coaching & Training

- Laura Caldwell Fellowship

- Current Athletes

-

Alumni

- Wallace Campbell

- Calista Ariel

- Chass Armstrong

- Trent Binford-Walsh

- Ryan Bugler

- Chris Caldwell

- Josh Cashman

- Shawnee Carnett

- Frank DeVar

- Nicole DiMercurio

- Kate Dodds

- Dylan Doss

- Ricky Flynn

- Emily Forner

- Adam Freudenthal

- Dylan Hassett

- Mark Leininger

- Mackenzie Lowe

- Zach Mains

- Cristina McKnight

- Avery Martin

- Tyler Morse

- Joe Niemiec

- Alison Parris

- Victor Pataky

- Annie Rodenfels

- Ryan Root

- Kimberly Ruck

- Austin Steagall

- Carolyn Watson

- Chelsi Woodruff

- Blake Wysocki

- Pics & Vids

- Sponsors

- Greenville, etc

- Social Media

RSS Feed

RSS Feed